Ryan Doherty’s lean frame stands in the doorway of 116 Barranca ave. He draws a deep breath, looks around the room filled with memories and keepsakes of an old friend, then shuts the door. A shockwave reverberates through the papier-mache-thin walls of the duplex he moved into 4 years ago after graduation from UCSB. To Ryan, it is more than a house or even a home. It's a gathering place for friends from near and far, a vessel for brainstorming the next adventure idea, and a bastion of creativity, looseness, and youthful spirit in a neighborhood that is quickly trading those tenets for poshness. Many people, including myself, have called that duplex on Santa Barbara’s mesa, just steps from Leadbetter beach, home, but the most important one, the one that left a lasting impact on him, is no longer here.

Ryan takes a seat next to me at the dining table. Outside it’s damp and grey, with a strong west swell throbbing through the Santa Barbara Channel, stirring up all kinds of frantic energy in the ocean and in the house’s residents. Inside the house is quiet and calm, as Ryan reflects on the early days of living there. He became especially close with one of his new roommates, Nick Simon, as they both shared a passion for adventure. Surfing, backpacking, skiing, and rock climbing were all on their list, but what they bonded over most were ideas for different bicycle touring routes, with Ryan having done Eugene, Oregon to Santa Barbara, and Nick having completed one across his home state of Colorado. What made Nick so remarkable though, was his demeanor. He was gifted in many ways, but always remained humble. He was loved by all, but always had time to listen and relate to what those around him were feeling. “He was one of those guys that when he talks, you gotta listen,” says Ryan.

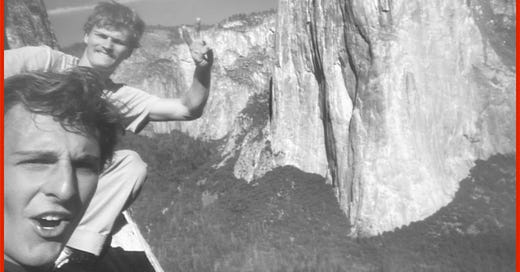

After living together for a year and a half, Nick quit his corporate day job and moved out of the Barranca house to pursue some adventures that had been on his mind. During a month-long road trip through New Zealand, the rental van Nick was driving was hit head-on by an erratic, inebriated driver. Ryan had just summited El Capitan in Yosemite when he received the news of Nick’s passing. With emotions swelling he tells me “It was the best and worst place to hear it…and I had this 5-hour walk back alone to try to take in, break down, make meaning, compartmentalize, rationalize, even lie to myself about what happened.” After feeling disillusioned with the typical grieving process over the next few days, Ryan decided the best way to honor his friend and sort through his emotions would be to take action. He organized a bike tour, just like the ones Nick and him used to fantasize over, from Canada to Mexico. Nick’s family had set up a GoFundMe, so Ryan could spread the word and ask for donations everywhere he went. Less than a week later, he bought a one way ticket to Canada.

Not long after, The Simon family created the Nick Would Foundation, a nonprofit that would support underprivileged kids in having meaningful outdoor experiences. The slogan “Nick Would” was chosen because of Nick’s action-oriented mindset, and serves as a reminder of how to use his legacy for positive change. A tagline on their website reads, ‘If you are ever wondering if you should go do that thing, help that person, or spread a little love, remember “Nick Would”.’ To date they've raised hundreds of thousands of dollars on their mission of ”expanding access to outdoor pursuits, wildland exploration, and artistic development to those who otherwise could not experience these activities for physical, mental, or economic reasons.”

Ryan would raise over $15,000 in his month-long bike journey. In addition, Ryan journaled extensively on his tour. The following excerpts are just a fraction of the complete volume, but they embody the emotion and meaning that motivated him.

-Lucas Grandcolas

CANADA TO MEXICO

By Ryan Doherty

There’s a lonely strip of highway that remains to the lost, the wanderers. A tangible, bold white shoulder exposes a distinct set of values between the wanders and the ‘others’. Anyone that’s within this narrow strip of asphalt can be perceived with a negative notion, a vagabond. I watch million dollar vehicles race by me with petty eyes, glossing over my bulky, steel frame bicycle , as if I’m lost. But I’m not lost, I’m incredibly in tune with my quest, my purpose. This sad shoulder of highway has enriched my life with meaning, and a deeper understanding for my dear friend, Nick.

Vancouver-Point Orchard; 186 miles

This will be my biggest bike-tour. Over 2,000 miles, solo. I study the topographic map, scanning each twist and bend from Canada to Mexico. A job too demanding for such a nice morning. I sit beside the cold fire pit, coffee in hand, underwear aimed toward the warm sun. A bit of comfort I’ll hold onto, I might miss this soon. My one-way ticket to Vancouver, Canada departs tomorrow morning, and I still need more gear. After Alaska, I was quick to reach out to my dear friend Dom McCloud, a friend of Nick. He had a steel-framed, Italian Bianchi ‘Velope’ road-bike. Over a decade old, the olive green tint still shins. Thick 700x-38 wheels would bare most debris along the highway. Four saddle bags would be packed full of marine wool socks, two shirts, a pair of sandals for California, travel guitar, bike parts and my prized, ‘cut too short’ jean shorts. I laugh, ‘feel good, ride good’ right? On top of that, a turquoise visor, spelling ‘ARIDE4NICK’ for everyone to read. The bike is outdated, yet perfectly sound for the ambitious mission. Twenty-six gears will alleviate the steep mountain climbing in Big Sur, and provide enough leverage to speed through the flat terrain in Malibu. A final touch before ying, I will add a hand carved slab of driftwood, spelling ‘CANADA TO MEXICO, DONATE TO GOFUNDME/ ARIDE4NICK’. By evening, everything is settled, the bike is ready, under one rule. I will repay Dom with dinner and cold beer; a deal I couldn’t refuse. The flight to Vancouver in the evening was my first mistake, for it’s too risky to ride at night. A midnight train to my cousin's apartment across town, an extra 40 miles for the following morning. As I wait for my boxed bike to arrive on the conveyor belt, I watch families race through the terminal. Eager to escape the fluorescent lights among their fellow passengers. As for me, no one waits, nor cares. I assemble my bike from a cardboard box before departing towards the city. The lights radiate from street vendors and I reach my cousin Laine’s apartment. In the morning, my adventure will start, for now, I will rest.

Jack Kerouac- Part One

I descend from Downtown Vancouver midday, aiming south along interstate highways, passing green flashing stoplights and Victorian homes. Curious eyes peek out from cathedral windows on Marine drive, estranged to my slow moving, bulky bike. I reach Coldicutt Park, where I look out toward Orcas Islands, as far as my eyes can see, trying to compartmentalize the future mileage. Lonesome bridges and massive ferries expedite my travels through the islands of Northern Washington. I decide for every lake I pass, a nude dip must occur, regardless of passing cars or Ospreys hanging around. South from Belfair Park, I gain closer distance to Olympia, Washington. A comfortable pace of fifty miles per day, the Bianchi has been working well, but the weight seems unfairly distributed between each bag. BOOM! The front rack snaps in half. Too thin and poorly welded, the lazy steel is unfixable. Two heavy bags drag along the asphalt, like a demolition car. A serious logistical dilemma; the bike is unrideable and three nearby bike shops don’t carry the rack I need. I widen the radius on my maps. Olympic Bike and Skate, 10 miles south. They have it. I do the math, a two hour walk, through the evening. Will the shop still be open? Evening time is creeping by, so I plug my thumb into the air. Within five minutes, I meet a lucky man. Nearly 70 years old, a retired veteran named Tug pulls over. A distinguishable white beard and an overly large belt buckle, he says, “I’m having a pretty rough day too, let me help you.” Tug was procrastinating his husband duties, a Sunday furniture restoration project. Instead, we merge together, passing by bikers and tourists. I watch the mile count grow. We talk about his tour in Vietnam, his new addiction for CNC machines and I thank Tug for the ride, thinking our time together would come to an end. Unpacking my bike, I walk toward Olympic Bikes but, this departure wasn’t the end of Tug, he would stay at my hip for however long it took.

The street swells with enthusiasm, a busy weekend for Port Orchard. I lean my broken bike against the shop window. On display, a sun-faint photo revealing a young man, standing proud beside a fighter-jet. Tug grew interested, maybe he knew him? The man looked young, and I think, this story will probably remain untold. The swinging glass doors opens, leading into Fred’s shop. An unordinary legend according to stories heard by Tug. A bell rings above our heads, then Fred turns our way. He stands in front of a pyramid of bikes, all tumbled onto each other, like a piling junkyard. Most in terrible condition, entwined with cobwebs and an aurora of mildew and rust; the shop reminds me of an episode of Hoarders. Standing close, Fred’s crooked teeth show a gap, his smile is enchanting. His calcified knuckles and leathered skin reveal a history of hard work. He wears a crusted, grease-stained shirt, also validating years of bike experience, I figure he’s worn those loose sweat-shorts and high calf socks too, for they are too heavily greased. I walk forward, Tug by my hip. The counter space is taken by bolts, tubes, old paperwork, fading receipts, phone numbers and loose change, and I introduce myself. “I’m Ryan, I called earlier.” “That’s right”, he says, pulling a bulky front rack from behind the wall of bikes. Exactly what I need! I ask, “who's the young man in the photo?” He says, “That’s me son, I flew that thing in nam.” The question sparks a chain reaction of stories, he details dogfighting stories, dropping deadly bombs on secret bunkers, taking 50-rounds of 50-cal bullets in the air. Stories of his partners, living by a ‘die proud’ mentality feels unworldly. Fred explains, “if we go down behind enemy lines, it won’t matter--we’re so god damn tough, no one, not even the Philippino’s could eat our meat, it’s too tough.” He was absolutely content with the idea of dying in line of fire, a hardened trait that escaping death by the thick of skin, swearing he’s the luckiest man alive.

Now, he weighs on his fate with Jesus Christ. It seems Fred is reliving this other worldly past, talking through his own stories, reminding himself of his own past. I listen with care. I chip in a question between war stories, “what was life like before the war?” Fred time travels, to his beatnik era. His posture straightens, as if he’s gearing up for a new chapter. Stories of hitchhiking on freights, across the country and back, absolutely broke and scrawny. A total dirtbag. He says, “people used to call me Red, for my scruffy red beard. It stuck for awhile. Especially when I befriended Jack Kerouac.” Tug doesn’t appear intrigued, as he takes interest in a Lee Jones novel. But my eyes widen, mouth agape. I’ve unlocked something incredible.

Jack Kerouac, a keystone for the Beatnik’s. He epitomized the deepest levels of this nomadic, frugal, simple lifestyle. A character Nick resonated with deeply. I remember his Big Sur, always close by. I imagine him from above, smirking and manifesting this connection to Fred. Enthralled and captivated into his own past world, as if Tug and I were invisible. He says, “Jack and I would converse, he would take on challenging topics, shared with early morning coffees in San Francisco’s City Lights Bookstore. Then one day, Jack left unexpectedly, hitchhiking East. I would never see him again, until l went back to school and saw a copy of On The Road on display, at my university bookstore. I flipped through the pages, and there I was. Red.” I chirp in a question, thinking of Nick and my own journey, “if you can go back in time and ask for Jack for advice to someone like me, on the road, what would it be?” He says, “Jack would say, life is all about experience, and what you’re doing right now on your bike tour is collecting a wide array of experiences. When you die, that’s what you have to look back at.” The simplicity in the answers feels oddly profound. Though I identify with this perspective, the advice reinvokes and reinforces my intuition, reminding me that Nick did it right. He held a magnitude of life experience, from his solo-international travels, to rigorous bike tours, to committing to deep, heavy barrels, to having anti-prejudice ideals, to exerting unconditional love to anyone around. Nick was an old soul, like Fred and Jack. I’d like to think in a different universe, Nick travelled on an empty freight train with Kerouac and Fred, heading nowhere with purpose and intention. With this, I feel my heart is a touch more healed. Tug grows tired, his posture is slouching now, it’s time to go. As we leave Fred behind, silhouetted by his pyramid of bicycles, he shouts, “God is great, he is a connector.” Everything in my soul believes otherwise; Nick brought me here, for he is the connecter from above, leading me to Tug, Fred, and Jack Kerouac. Tug will not continue south with me, he must finish his Sunday errands. I plug my panniers onto the new sturdy rack and aim for Astoria, Oregon.

Ferlinghetti and Kerouac - Part Two

After my close call with the Rottweiler, I pedal far into the evening. Fifteen miles north of Arcata, I try to rationalize the distance. I hate to be biking in the dark, but I have no way out. The shore is too windy, too loud, too rocky to sleep on. The Pacific Ocean feels more erratic than ever, blowing vicious onshore, cross-winds toward my narrow shoulder lane. My legs still fail to recover from the feral dog, and I feel like shutting down. Nights have been cold on the beaches, and the heavy dew fills the morning air, wetting every item I own. A setback in morale. I pull off the highway, finding a touch of protection underneath a construction dozer. I call my brother Evan; an eccentric 27 year old. More frugal than Kerouac himself, he has traveled solo around the world, more than anyone I know. He holds a bright inner compass, always finding other bright souls with an effortless, deeply charismatic personality. Similar to Nick.

He forwards me a number. A fellow traveler whom he met in Mexico a year prior, he tells me she might still live in the small coastal town of Arcata. Her names Aurora Ferlinghetti, and I dial her three times before she picks up. I imagine her reaction. The contemplation of letting the brother of a stranger, whom she never really knew, years ago in a foreign country stay in her quiet home. But the hesitation lies between us both, for I’ve been deprived of human interaction since Canada. The lack of companionship has hardened my character, part of me prefers the isolation, but the thought of dewy, wet clothes tells me something different. I keep it short on the phone, explaining my Ride-4-Nick journey. She agrees to host me just for the night. I accept the open couch, as long as I’m protected by the wind. I put my wet phone away, and pedal into the dark, stormy night.

On the east side of town, nestled below the Arcata Community Forrest lies the home of Ms. Ferlinghetti. Unlike the fluorescent lights of Sunset Beach, Arcata’s streets remain dim. The bright moon casts a soft shade of light, just enough for a stranger to find his way. I near the curtain of towering Redwoods, all surrounding Ferlinghetti’s small, wooden home; guardian-like. I park my bike along the house, unlocked and uncared for. I am too tired to worry. The strangers home is disguised by the towering trees, it feels like a dream. Plants spill over the redwood deck, while green vines twine around the soft wooden handrail. A row of abalone

shells lay along the footpath, sparkling with radiant blues and purples from the moon. A collection of tall, cathedral windows show flickering candles inside, revealing an antique record player, an eleven foot hand-shaped Mark Andrenni longboard held over an enormous bookshelf, tightly filled with all sorts of paperbacks. But my eyes gravitate toward the single copy of Kerouac’s ‘On the Road’, laying beside an astray of spliffs, I question the coincidence. Ms. Ferlinghetti opens the door softly. The rain continues to pour, louder than before, and without an exchange of words, she lets me in her home, rescuing me from the storm. Half Filipino, half White, Ms. Ferlinghetti stands tall. A pendant of Jade shines from her sternum; a rare stone Nick tirelessly searched for.

We sit on the couch, loudly quiet. I feel a slight delirium, overwhelmed from the dark interstate highway, just an hour ago. She hands me a thick wool blanket, and hot tea. I break the silence, hinting towards the Kerouac novel, “have you read the piece?” An easy and quick topic to speak of, though my mind fades to Fred and Jack, two unorthodox heroes. She says, “I’ve read a lot of Kerouac. More than most, I’d say. I find it fascinating that a person could appreciate Kerouac’s brute lifestyle, I’m sure it only feels fitting to read his piece while being on the road.” I sense Ms. Ferlinghetti shares a similar passion for his literature. Her calloused feet, tan skin and sun-highlighted hair help prove my point. She adds, “I appreciate what you’re doing, Ryan. Even though I don’t really know you, I felt it was important to host you. A touch of comfort can go a long way.” I feel a sense of safety and protection from this stranger. The Earl Grey tea slowly warms my pruned fingertips, then Ms. Ferlinghetti stands, dancing swiftly to the kitchen. I watch her faded denims hover above a beautiful abalone anklet. I watch her stir a warm pot of chicken noodle soup. I press off the couch, taking a deeper look into the collection of books. An array of authors, most I cannot recognize, though I find Devin Quinn, Richard Powers. Then a string of Edward Abbey, and more Jack Kerouac. I finally relay a shortened version of my indirect experience with Kerouac.

She says, “You might not believe it, but I have strong ties with Jack Kerouac myself.” I couldn’t imagine a more strange connection than myself. Impossible. “My grandfather Lawerence Ferlinghetti knew him well, would support and offer a place for Jack to stay and work. They shared a passion for poetry and outdoors. My grandfather was an incredible poet, painter, social activist and even owned City Light Bookstore, where lots of Beatniks would hangout. Through his career, he made home in Big Sur, California. A quiet, little homestead in the hills, where he would write. I visit whenever I get the chance.” She adds, “he would let Kerouac stay there too, providing a sanctuary for the beatnik to visit, Jack would hitchhike south from Sunlight Cafe. This is where he would draw inspiration from and eventually write his Big Sur novel.”

I struggle to conceptualize such strange coincidences. Ms. Ferlinghetti’s grandfather might’ve known Fred too, I laugh at the idea, the corky old man doesn’t surprise me. Kerouac’s presence seems to be integral in this bike journey; another strong reason to believe Nick’s spirit could be responsible for the coincidences, for connecting me with a famous beatnik who passed decades ago.

What can all of this mean? I keep relaying this tough question internally as Ms. Ferlinghetti speaks, but I can’t find the words to explain it. To comprehend this strange connection, I know I must continue riding south. For only time and isolation could draw deeper meanings to such

outrageous serendipities. I rely on this. Before Ms. Ferlinghetti finishes her story, a knock at the door reveals three friends. She forgot it was card night. I grin, absolutely content, full of Nick’s spirit within. I do not need anything more, just another bowl of warm chicken broth. I fall asleep to soft laughs and shuffling cards, a perfect ending to a perfect day. The following morning, the house is empty. Blue Jay’s chirp from the windowsill and Ms. Ferlinghetti has left to find swell for a sunrise surf; I reassemble my bike, and continuing biking southbound for the rest of the day.

Santa Cruz to Monterey

Weather begins to change as I reach the central coast. Half Moon Bay remains in a pocket of fog, just as I remember as a kid. Home to one of the world's largest waves, Mavericks. A powerful, dooming wave, measured beyond scale. The surf town surges with energy when wave forecasts align, then local heroes test their courage against the gravity defying wave. I partly fantasize over the lifestyle of the surf town, where cypress trees grow quietly and the cold water provides an escape for all water-people. Life feels simple here.

As I continue south, the vast ocean fades away to the barren valley of Salinas. This stretch feels slightly different. I hold Steinbeck’s rhetoric responsible; for his novels, East of Eden and Grapes of Wrath have drawn difficult-to-find beauties from the harsh land. Steinbeck saw the valley as a microcosm of broader human struggles, particularly relating to land, labor, and survival. He recognized the underlying tension between wealth and poverty, landowners and laborers. A playground caved by unjustified greed. The valley draws strong wind from the west and I notice my chain building with dust and grain. Never-ending terraces reveal infinite crop. The sweet smell of strawberries and artichokes flood the fields, but this growth is contingent upon the hands that picks it.

I watch their bodies from my moving saddle; bent at 90 degrees, L-shaped and entwined with heatwaves, ever so stagnant. The heat is inescapable, impossible to avoid. I try to empathize. As a wildland firefighter, I share a similar line of work: long hours, physically demanding labor, para-military values, isolation, excruciating heat, emotional taxation, low pay, etc. Though my life is incomparable. The cards I’ve been dealt are wildly opposite. How is it that another human, meters away is working to survive, to support a family, even evade authorities against unjust immigration rules. The gap between wealth and poverty, as Steinbeck acknowledges is overtly present. How should I feel from the saddle of my bike? Is this ride appropriate? How is this fair?

The beauty of tour riding is that you see such economically diverse areas, revealing an underlying truth; that empathy is an important keystone to living a soul-filling life. One must respect and help others in need, stay humble, learn to spread love to all those around; this seems a powerful lesson here and I know Nick would agree. I tip visor to the working bodies in admiration. Nick’s ‘Farewell’ song plays in my earbuds, “it’s easy to get caught in stagnation, a place where the weary go to die. Gotta keep moving if you want to see clear, that’s why I had to say goodbye.” He understood the importance of moving; to see more clearly.

“The Greatest Gift of All”

My 1998 Ford Ranger idles in the driveway, she’s mine. A prideful feeling, for the sun-baked hood and low clearing undercarriage. Four cylinders and slower than most, I love her. I construct a makeshift bed frame, with sliding drawers underneath. I’ll be living out of it for the upcoming fire season. It will be my first season as a wildland firefighter for the Los Padres Hotshots, in Santa Barbara. My housemates know the deal, 6-7 months gone. I will be working the hardest job in the world, in hopes to finance my first Patagonia climbing expedition the following winter.

The housemates gather around the truck, it’s time to go. I hug each of them: Matt White, Gavin, Andrei and Nick Simon. I say my farewell, and before reversing, Nick runs back to the truck, blocking the driveway. His smile is incredibly vivid. His large frame gently squeezes through the truck window, like a bear, giving me a final hug before leaving. He says happy early birthday brother, before anyone even knew. Only Nick. He hands me his own copy of “Drifting West”, an incredible story written by our dear friend Stevie Page. We exchange a final smile, both acknowledging the embarkment that we are each going to endure. Months later, I find a folded slip of paper in the spine of the paperback. A hand written card. This note has become my most valuable piece of property. Written to me, it catalyzes Nick’s essence in such few words.

His note reads, “Your energy and passion for living life is so contagious and you constantly inspire me to get after it and to stay present. I’m so grateful for this last year of living with you and all the unforgettable experiences we have shared. From middle cathedral and el cap to Big Sur to sb and everything between I’ll miss you as we both embark on the next chapter and become better men. I’ll be thinking of you when shit gets fucked there, but I know we’ll come back even hungrier for adventure then before.

Keep er’ pinned till the wheels fall off brother.

Love, Salmon Boy”

“Kissing the Finish Line”

I turn at a four way stop, I see it. The border wall. Symbolizing to my true end. A dirt road leads me along the ominous looking wall. It soars high, higher than any structure nearby. Unclimbable.

The slick metal illuminates an earthly, rustic color, mirroring the rich Californian dirt below. I imagine the finishing line, where roses are thrown, beers are cracked, and friends rejoice, but this ending is far from that. It’s lonesome and brutally quiet. Nobody greets me, only my dear friend Tyler Hanson. But this is okay, it’s how I envisioned the finish. I wanted to expand, and deepen my understanding of the trip. A finish line filled with friends, and stimulating energy might inhibit my chance to feel Nick’s presence one last time on tour.

The border wall lashes into the sea, and the Pacific Ocean greets me. A familiar, calming presence, one that eases my mind, for the ocean saved me through my longest days. A border patrol agent hides in his vehicle nearby, stalking all possible movement, like a hawk. Trained to expose any human who dares to cross his path. He glimpses at my heavy bike with a stern expression. He will not be congratulating my journey, but I cruise by anyways, feeling intense eye contact. The “Trump Border” doesn’t sit well with my stomach. I yearn for sadness, realizing how tough life might be along the other side, just 50 meters away. A rich country that’s been discriminated against for endless generations, where families flee for prosperity, yet endlessly denied. I imagine Nick biking alongside, feeling the similar pit of guilt. I think about the billionaire dollar trust-fund babies in Beverly Hills, whom I passed. I hope this harsh reality can spark feelings empathy for them. As I bike parallel, wide gaps between the thick metal reveal Tijuana’s landscape. Colorful homes settle among the terrace, facing outward to the Pacific Ocean. A magnificent view. Priceless. An identical view to the million dollar oceanfront homes in Carmel. Maybe these families live in peace, in harmony of the land and ocean. Who knows, but I will not speak for them.

A seagull lands on top of the unclimbable wall, free to explore these two different worlds. I imagine how precious that freedom would feel for all humans. I wonder how empathetic the patrol agent is; what if his role was switched with an immigrant for the day? I finally reach the beeping security gate, finished at the border of Mexico. It’s incredibly quiet. Despite my feelings of finishing solo, I do feel lucky to have my friend Tyler nearby, otherwise I’d have to bike 20 miles north to the nearest train station. That will suck. We share a laugh, I finish my warm Modelo, and I’m instantly reminded how sweet it is to have friends. I pack my worn down Bianchi into his van, holding onto her as if it mattered anymore. I don’t want to let go. I don’t want to finish, I want to continue. I want to ride to the end for the world, for Nick. I feel I could bike forever, all the way to Patagonia if I had enough time and money. The warm, tall Modelo relaxes my irrational thinking. I am done, and I will sleep at Tyler’s, take the train to Santa Barbara the following morning. A five hour train-ride will cover my previous five days of biking; that feels wrong.

The train stops in Santa Barbara. The doors open, leading me back into the world again, like a snapshot. My sturdy legs buzz between strides, as if I’ve forgotten how to walk. But here I am, back in the world of walking, where my bike accomplishment will remain unannounced to strangers who don’t ask, like Fred’s sun-damaged photo in Port Orchard, Washington. I imagine this is how Nick felt when he finished his Colorado Divide Tour: an innate sense of humbleness, an inability to boast, and a heart full of love for others. I will bike home from the train station in

silence, in honor of him, acknowledging and relaying his motto, indefinitely. I walk away from this adventure uninjured, a true blessing, and I thank that friend above for watching over me. A million lessons learned, but one stronger than most is a new understanding of empathy. I experienced many sides of humanity, solely from the saddle of my bike; from the billionaires in Los Angeles to the poverty stricken families in Oregon, I’ve passed through it all. This journey has posed a new, important revelation to my own life, that empathy is key to living a prosperous life; it’s a trait that every human must have, regardless of their status. It strengthens our soul, connects us. It’s absolutely critical, and is not a coincidence that Nick Simon embodied this more then most. His life was balanced between adventure and empathy.

I reach my final stop. The home where Nick and I once lived together. Where his energy and love grew wild, like the Oak Moth Caterpillars that’ve taken over the backyard. The small surf house has grown quiet now, the staircase doesn’t creek with exciting feet as much. I tuck away my heavy bike into the overgrown side yard; bike-touring has come to a halt. I must continue the Pacific Coast Search, for Nick and myself. Brined with salt from Alaska and thousands of hard earned miles, I cinch Nick’s Filson hat tighter, and fill my cabover camper will haul bags, full of rope and climbing equipment, I head for Yosemite Valley’s colossal walls to dive deeper into my past.